Iranian Animation and the Art of Dissent

By Millad Khonsorkh

21 May 2025

The global recognition and Academy Award for Best Short Animation of In the Shadow of the Cypress (Shirin Sohani & Hossein Molayemi, 2023) isn’t just a victory for Iranian animation; rather, it’s the latest in a long-standing tradition of resistance through art. For decades now, animation in Iran has provided a medium that allows boundaries of censorship to somewhat dissolve, where the weight of silence can find expression in surreal landscapes and allegorical narratives. Its most innate qualities – the lack of human faces on screen, the ability to express through abstraction, metaphor, and illusion – are exactly what allow animation to become such a subversive instrument for expressing ideas, stories and truths that official discourse seeks to erase.

In its lack of dialogue, for example, Sohani and Molayemi’s Oscar-winning film affirms the enduring power of animation to bear witness when words are not enough. Those of us fortunate enough to have never experienced war may find it hard to grasp the idea that a war doesn’t end when the fighting stops. This is the powerful truth at the heart of In the Shadow of the Cypress, which shifts its gaze inward, exploring the quiet devastation of a father suffering from PTSD. His rage has no target, no enemy; it ricochets off the walls of his home, injuring his daughter and poisoning what remains of his humanity. He is a man crushed by the machinery of political violence and erased even from memory.

Iranian animation repeatedly returns to this theme: the inescapability of history, the way personal suffering becomes collective inheritance. The film's apparent quietness in not using dialogue sits in stark contrast to the constant noise that we understand to afflict the two characters here. This achievement stands at the crossroads of legacy and innovation, signalling the culmination of decades of artistic experimentation and what could be the beginning of a new era of Iranian animation.

"Freedom always comes at a price. But what if it costs you everything?"

—Tehran Taboo (Ali Soozandeh, 2017)

In The Shadow of the Cypress – Shirin Shohani & Hossein Molayemi

Read our interview with the Oscar-winning filmmaker duo here.

A potted history of Iranian animation

Powerful and successful Iranian animation is not a new phenomenon, however. The country’s first animated films date back to the 1950s and, like many cartoons worldwide, were geared towards children. The oldest remaining animation from this period is a fifteen-second clip of a heroic, humorous folklore character, Mullah Nasrodeen. The first animation studio was founded in 1959, and throughout the 60s and the 70s, before the Islamic Revolution in 1979, state-sponsored studios such as Kanoon and the Ministry of Culture and Arts produced educational and folklore-based animations such as Malek Jamshid (Nosrat Karimi, 1965), Zendegi/Life (Nosrat Karmi, 1966), Shahr-e Khakestari/Grey City (Farshid Mesghali 1972) and Siah Parandeh/Black Bird (Morteza Momayez, 1973), with many of the animators of this time having been educated in the West.

This era saw two divergent aesthetic tendencies, one inspired by medieval Persian miniature painting and other classic art forms, evident in the work of Karimi and Ali Akbar Sadeghi, and the other having a more modernist spirit, as seen in the experimental figurative work of Mesghali. The lack of equipment and training meant that Iranian animators had to innovate within their constraints, often leading to a unique yet technically limited animation style.

However, after 1979, it wasn’t just technological constraints that animators had to contend with. As artistic expression became heavily monitored, like all other forms of media, animation was forced to adapt. Many filmmakers turned to allegory, crafting works that could pass under the radar of censorship while still maintaining some form of critique within the shifting social and political landscape. Up until the noughties, animators continued making didactic shorts, similar to the state-funded animations made before the Revolution, focusing on imparting moral lessons and cultural values.

Yet animation, through its very nature, allows artists to be much more forthright in their expression and critique of Iranian society. Persepolis (Marjane Satrapi & Vincent Paronnaud, 2007) is probably the most famous Iranian story to do so. An autobiographical coming-of-age story set in the period just before and following the Islamic Revolution, Persepolis tells the tale of a young, spirited girl witnessing the social and political change occurring in Iran at the time.

From the very first scene, the stark black-and-white aesthetic seems to mimic the flattening effect of authoritarian rule; there is no space for nuance, no gradation of experience. Its very power lies in its superb elegance and simplicity, the urgency of both the storytelling and the method of storytelling. The film’s greatest defiance is perhaps in its global reach – its release was met with both acclaim and controversy, with Iranian officials condemning it as propaganda, while audiences around the world resonated with its ability to merge personal and political reality.

Persepolis – Marjane Satrapi & Vincent Paronnaud

The art and craft of evading state repression

The 2010s saw the rapid expansion of digital technology and a rise in underground filmmaking, allowing artists to push creative boundaries even from exile. Ali Soozandeh, an Iranian living in Germany, used rotoscope animation – a technique where artists trace over live-action footage frame by frame to create realistic motion – in Tehran Taboo (2017) to circumvent filming restrictions and depict a Tehran both shocking and truthful. His use of rotoscope allows the viewer an almost documentary-like view into an Iran unimaginable to the outside world. The film extends the suffocating childhood repression seen in Persepolis into adulthood, mapping out a city where the rigid laws of the state are negotiated, manipulated, or outright ignored.

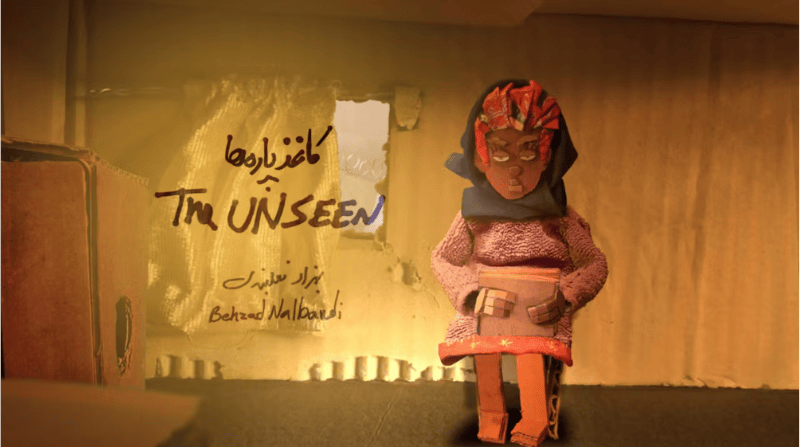

Iranian animation often lingers on the margins of visibility, illuminating those who society would rather forget. The Unseen (Behzad Nalbandi, 2019) chooses to abandon traditional animation techniques in favor of stop-motion and cardboard figures, its rough textures mirroring the fragile existence of its subjects. The film, which at just over one hour sits somewhere between a short and a feature, exposes a cruel reality: that women deemed undesirable, be they sex workers, drug addicts, or homeless, are forcibly rounded up and detained, where they disappear into state-run shelters under the guise of urban beautification. The city, much like in Tehran Taboo, is a place where certain lives are deemed disposable. But unlike Tehran Taboo, which moves within the realm of fiction, The Unseen offers something uncomfortably real. It asks not just who is seen, but who is allowed to exist.

Another Iranian animator Shiva Ahmadi took inspiration from old Iranian art, her work often mirroring the patterned design of Persian miniatures and including embedded depictions of war, corruption, or religion. Her 2017 short animation Ascend, was inspired by the death of Aylan Kurdi and the crisis that caused mass migration from Syria in 2015. Another example of this within Iranian cinema is Our Uniform (Yegane Moghaddam, 2023), a 7-minute short film that uses the very fabric of the filmmaker’s childhood school uniform to succinctly reflect upon gender, autonomy, and society’s restrictive fashion rules. Characters, stories, and social commentary are all explored through the wrinkles, fabrics, and clothes of her youth, a thoughtful look at expression and oppression that would be difficult to achieve in any other medium.

Our Uniform - Yegane Moghaddam, 2023

In these films, and like in so many others, history is not an abstraction; it is a force that lingers in the air, seeping into the present. The Siren (Sepideh Farsi, 2023) doesn’t merely depict war; it allows war to inhabit every frame, every silence, every absence. Its protagonist, a teenage boy named Omid, refuses to leave Abadan, a city slowly crumbling under Iraqi bombardments. The war does not unfold as a series of battles but manifests as something more insidious, an ever-present force that eats away at the city’s soul. Without the use of animation, Farsi would have struggled to tell this story. Even with it, both she and the film’s screenwriter are currently exiled and unable to return to their homeland. Whilst animation can’t protect people from authoritarian rule altogether, it nevertheless provides a medium of resistance through art.

These films do not simply depict oppression; they actively resist it. Animation, which is still often dismissed as a medium of fantasy, is a vehicle for revealing unsettling truths. It bypasses the limitations of live action, making the invisible visible and, to some degree, rendering censorship powerless. The stylistic choices, black-and-white minimalism, rotoscope realism, and collage-like textures are not aesthetic decisions alone; they are political gestures, different ways of reclaiming the right to bear witness.

Persepolis draws from underground comics and protest art, its simple, expressive lines contrasting the complexities of its themes. The Siren employs flattened, almost dreamlike imagery to transform war-torn Abadan into something both mythic and immediate. The Unseen embraces the crude, unfinished texture of cardboard, reinforcing the impermanence of the women it portrays. Each film finds its own method of resistance, its own language of defiance.

Animation is not an escape from reality but an alternative way of documenting it, one that refuses to let history be dictated solely by those in power. In a country where speaking out can carry grave consequences, these films persist, pushing against silence with ink, with paint, with shadow and light. Their existence is a testament to the resilience of those who create them, to those who refuse to hide away, and who, in their own way, urge us to do the same. Authoritarianism thrives in darkness, and Iranian animation continues to shine a light on its darkest corners.